Recap

For a quick recap, we’re in the third week of our series called War & Peace, a series where we’re trying to figure out what the Bible has to say about matters of violence and conflict and hostility and justice and forgiveness. And what we’ve learned so far is this.

The very first and last thing the Bible has to say about war and peace is peace. Violence was not in the beginning and it won’t be in the end, because while we find violence fascinating, God doesn’t, and while we find peace naïve and boring, God doesn’t. That said, we live in a world filled with war and violence and faced with such a world, God’s peace moves forward by forgiveness instead of vengeance because God’s goal is not revenge but reconciliation.

And it’s almost impossible to properly emphasize just how radical a thing this is—that Christians believe in a God who would rather die for his enemies than give them what they deserve. That Christians believe in a God who desires to embrace his enemies in the arms of forgiveness.

And while that’s the most beautiful thing any of us could ever hear, here’s where it gets hard. Christians are not just called to accept God’s peace and forgiveness—we’re called to practice it, we’re called to embody it, we’re called to be a community that lives out God’s peace and forgiveness right smack dab in the middle of our families and our workplaces and our towns and our nations. Last week, we talked about what God’s peace does when confronted with a world at war, and so this week we have to talk about how we (the church) practice God’s peace in a world at war.

The Sunflower

During WW2, Simon Wiesenthal was a Jewish inmate at a concentration camp in Poland when he was asked to do the unthinkable. He was led down a hallway and brought to a room where a young Nazi soldier was dying. And in the moments before his death, this Nazi soldier wanted to confess his sins and receive forgiveness from a Jew.

And so as Simon stood at the bed of this soldier, the soldier started confessing his shame at being a Nazi and admitted he’d been a part of a group that had rounded up hundreds of Jews into a house and then set it on fire, burning them all alive.

And as Simon listens to the confession, he’s moved by the soldier’s grief and shame but sickened and repulsed by the things he’s done. So Simon listens in silence to the confession and when the soldier finishes, Simon walks away without saying a word—certainly not a word of forgiveness.

Years later, Simon wrote a book called The Sunflower where he tells this story and then ends by asking the question: what would you have done? I’d like us to take up Simon’s challenging, troubling question this morning and think about it as the church, as a community of people who follow Jesus: what should we have done? We’re going to use two important texts from Matthew to help us move toward an answer: Matthew 18:21-22, 5:43-48.

Matthew 18:21-22…70 x 7

So Peter comes up to Jesus and asks him, “Jesus, how often should I forgive one of my brothers when he sins against me? Should I forgive him as many as seven times?” Peter clearly thinks he’s made a very generous proposal, and I have to agree—I mean, forgiving somebody seven times is a lot, isn’t it? Can you imagine forgiving your spouse seven times for cheating on you? Can you imagine forgiving your buddy seven times for roundhouse kicking you in the face? Both of those things would be hard for me, so I think Peter is being awfully generous.

And yet Jesus has other ideas, so he says, “Actually Peter, you shouldn’t just be willing to forgive somebody seven times but seventy-seven times.” Jesus is alluding to Genesis 4:24, where Cain’s great, great, great, great, great grandson, Lamech, brags to his wives that if anybody messes with him, he will seek 77-fold vengeance upon them. If you roundhouse kick Lamech in the face, he would roundhouse kick you back 77 times.

Jesus’ point here is clear. Our capacity for forgiveness toward each other (in the church) must be deeper than even the world’s capacity for vengeance. Do you have any idea how deep the world’s capacity for vengeance is? How far people will go to seek revenge? Of course we do, because we’ve felt it—that primal, gut reaction of rage that wants to track down our enemy to the ends of the earth to get them back.

Yes, we know the world’s capacity for vengeance, which is why we’re shocked and stunned when Jesus says we’re supposed to be more serious about forgiving than Liam Neeson is about revenge. We’re called to be better at forgiveness than the world is at vengeance. In the church, forgiveness is willing to move toward infinity. And now Matthew 5:43-48.

Matthew 5:43-48…Love Your Enemies

So as if having a capacity for forgiveness within the church that moves toward infinity is not enough, now we have to deal with this—a teaching from Jesus that seems so ridiculous and impossible that Christians have been trying to explain it away for 2000 years.

What Jesus says is really clear. You’ve been told that you should love “your ppl” (friends, family, fellow Jews) but that you have permission to hate the people who hate you…you have permission to hate your enemies. But this is what I’m telling ya—not only do you not have permission to hate your enemies, but I’m calling on you to love them. Love…your…enemies.

It’s perfectly clear and yet seems so impossible that it makes people invent ways to explain why Jesus didn’t really mean it. Well, Jesus is just talking about how things will be “one day, in heaven” and not commanding us to actually do this now. Or, these words just apply to a special class of holy Christians like monks and nuns, but not the rest of us. Or, Jesus is just trying to make us see how impossible it is to live up to God’s standards; he’s not expecting us to really do it. He’s expecting us to try to love our enemies, go “Well I can’t do that…so I sure am glad Jesus died on the cross for me so I don’t have to.”

And yet none of these interpretations will do because Jesus is most certainly telling us something that he expects us, and all of us, to do, here and now. And not because of some vanilla notion of “human rights” or “humanitarianism” or because “it works” and makes our enemies like us. No—all of that is beside the point. Jesus expects us to love our enemies because God loves his enemies—period. Nothing shows that you’re a child of God more than your willingness to love your enemies. It’s not the cherry on top; it’s not a secondary issue. Loving your enemies is at the very heart of what it means to be Christian.

We Believe in Jesus—Not His Ideas

A few years back, a man named Miroslav Volf wrote a book about all of this called Exclusion and Embrace, where he examines our difficulty embracing Jesus’ teachings about forgiveness and how to treat our enemies, and he says something that has haunted me for years: “We may believe in Jesus, but we do not believe in his ideas, at least not his ideas about violence, enemies, and justice.”

In other words, we’ll believe (generally speaking) that Jesus was God dying on a cross for our sins, but we don’t really feel obligated to take Jesus seriously when he tells us to pick up our own crosses and suffer for others through costly forgiveness and love of our enemies. We’ll believe that Jesus was crucified for me, but don’t really believe we’re supposed to be willing to be crucified for others. Crucified Jesus is good for the inner, personal world of our souls, dealing with our guilt, but doesn’t really have anything to do the social world we find ourselves in. Crucified Jesus is for “in here, saving me, after I die”, not “out there, for others, now.”

We’ll believe in Jesus but not his ideas because we know that if we do, it might cost us dearly—it might cost us our lives, right? But friends, we shouldn’t be too surprised if forgiveness and love of enemies cost us our lives—it cost God his. What do we think Jesus meant when he said, “Pick up your cross”?

This is Hard

And at this point, I’ll say what we’re all thinking: this is hard. In fact, I’ll go out on a limb and suggest that if something in you doesn’t revolt against the very thought of loving your enemies unto death, then you don’t understand what you’re being asked to do.

Loving the classmate who continually tries to humiliate you? Loving the parent who abused you? Loving the co-worker who betrayed you? Loving the ex-spouse who cheated on you and then took the kids? Loving the terrorist who wants to kill you? These things are impossible, right?

Portraits of Reconciliation

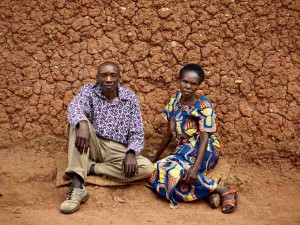

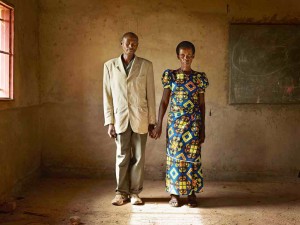

Earlier this year, a photographer named Pieter Hugo went to Rwanda, which was the site of a horrific genocide in which nearly a million people were killed. It had been 20 years since the genocide, and what Pieter found there can only be described as a miracle.

Over the last 20 years, many of the perpetrators and victims have gone through a very long, difficult, and heart-breaking program of counseling that ended in the granting of forgiveness and attempts at reconciliation. And in a remarkable series of photos, perpetrators and their victims were willing to be photographed together—stunning portraits of forgiveness and reconciliation (check all of them out here).

This is Jean Pierre and Viviane. Jean Pierre killed her father and three brothers. After being released from prison, Jean Pierre went to Viviane and asked for forgiveness and Viviane now lives in a house Jean Pierre built for her.

This is Godefroid and Evasta. Godefroid burned her house down and tried to kill her and all of her children. Evasta said, “I used to hate him. When he came to my house and knelt down before me and asked for forgiveness, I was moved by his sincerity. Now, if I cry for help, he comes to rescue me. When I face any issue, I call him.”

This is Francois and Epiphanie. Francois killed her son. Epiphanie said, “I used to treat him like my enemy. But now, I would rather treat him like my own child.”

And this is Dominique and Cansilde. Dominique chased her and her children out of her home and destroyed it. Years later, Dominique came and asked for forgiveness and Cansilde said, “I have nothing to feed my children. Are you gonna help me raise my children? Are you gonna build a house for them?” The next week, Dominique came with a group of others who were involved in the genocide, and they built Cansilde and her children a house.

A Word to Your Inner Skeptic and Realist

And instead of commenting any further on these photos, I’d just like to speak to your inner skeptic and realist for a second and say: Don’t tell me forgiveness and love of enemies is impossible. I know I don’t know your story. I know I haven’t seen what you’ve seen. I know I don’t feel what you feel. I know I don’t understand all your reasons. But I do know that God died for his enemies and he’s still out there, giving his children strength to do the same.

I’ve seen it happen in Rwanda and I’ve seen it happen with many of you. After last week’s sermon, one of you came up to me and told me the story of how your son was viciously physically assaulted, almost losing his finger in the altercation. And you knew who did it and wanted to go give him what he deserved, wanted to take his life from him. But then a soft, strong voice from deep within spoke to you and said, “God says to forgive.” And you’re learning to do it.

So I don’t know about you, but I’m sick of the skeptics and self-appointed “realists” running my life, telling me what is and isn’t possible. Is forgiving and loving your enemies the hardest, wildest thing you could ever begin to imagine? Yep. Is it impossible? Not even close.

Up Close and Practical

Now having said all of this, I want to take a few moments to get up close and practical because it’s very important to me, and more importantly to Jesus, that we be a community that is known for the way we forgive. Jesus wants Vista to be a place that’s known first and foremost, not for our music or cool building or whatever, but for being a place where the miracle of reconciliation is a regular occurrence. It’s what we do best.

And dare I say—if we got as serious about forgiveness and reconciliation as we are about politics and sports and status…the world might just believe we have some good news for it.

And so to get the ball rolling on this, here’s what forgiveness is and isn’t and how we might practice it.

(Not) Forgive and Forget

First off, forgiveness is not just forgive and forget. This whole notion of forgive and forget is, quite frankly, a cheap imposter for what the Bible teaches us about forgiveness. It asks too little and heals too little. Forgive and forget carries with it the naïve notion that, “Well, nobody every really does anything that bad to you, and even if they did they couldn’t help it and didn’t really mean to. And besides, it would be much healthier for you, psychologically, if you just let it go. It’s not a big deal, so heal yourself of your hate by forgiving and forgetting.”

And all of that is nonsense—equal portions denial and therapeutic narcissism. As Desmond Tutu says, “Forgiving and being reconciled are not about pretending that things are other than they are…True reconciliation exposes the awfulness, the abuse, the pain, the degradation, the truth. It could sometimes make things worse.” Christian forgiveness never sticks its head in the sand, never belittles the pain and suffering of victims, never suggests that anger and even hate be stuffed down and hidden from God. Anger and hate belong before God because only then can they be healed.

Exclusion and Embrace

So forgiveness isn’t forgive and forget, but rather it is exclusion and embrace. So much to say here, but I’ll leave it at this. True forgiveness judges sin by telling the truth about it. This is exclusion—doing what you must to step away from the one or out of the situation that has wronged you so you have the space to tell the truth about your pain and hurt and to stop it from happening.

But once it has excluded (and sometimes that has to be for a very long time), Christian forgiveness then desires the unthinkable: that we could learn to embrace the one who has wronged us. As Miroslav Volf says it, “Christian peace is not just the absence of conflict sustained by the absence of contact, but is communion between former enemies.” In other words, God’s desire isn’t that we avoid hate by pretending we don’t have enemies or by avoiding them. God’s desire is that we do what he did on the cross: open our arms in love and forgiveness to embrace our enemies even though they’re most certainly not innocent. God’s desire is reconciliation.

Forgiveness is a Life

So that’s the first thing forgiveness isn’t and is. The last thing I’ll mention is this. Forgiveness is not a feeling, a moment, a word, or an act. Forgiveness is a way of life, cultivated by God, in community, through specific habits of reconciliation.

It would be nice if forgiveness was just a feeling, moment, word, or act, but we all know better. No sooner have we opened our hand in forgiveness than we find our open hand has again turned into a clenched fist that we’re punching somebody in the face with. This is one of the deepest struggles of marriage—we’ll forgive alright, until we don’t feel like it. C.S. Lewis says it well: “To forgive for the moment is not difficult, but to go on forgiving, to forgive the same offense again very time it recurs to the memory—there’s the real tussle.”

If you want to be a person who lives and breathes forgiveness, then you must commit yourself to a community that practices it, over the long haul—daring you to shake the hand of the one who lied to you, call the family member who wounded you, even pray for the one who hates you. Forgive toward infinity, love your enemies, pray for those who hate you—it’s certainly easier said than done. But together, by the grace of God, it most certainly can be done. It must be done.

Response

I hope that this morning might be a lingering reminder of our most holy calling to be persons and a community of forgiveness and reconciliation. Some of you carry some very heavy stones of unforgiveness around your neck and have already thought of people you need to begin the process of forgiving.

But some of you don’t carry big stones of unforgiveness around your neck so much as lots of small pebbles of unforgiveness in your pockets. It’s low-grade hostility and animosity as a way of life. You don’t hate your parents—you could just care less about them. You don’t have any mortal enemies—you just don’t have really have any friends…you live in a world of strangers, slightly suspicious and hostile toward everyone.

But whether you’ve got stones or pebbles or both, here’s what I’d like us to do this morning and then keep on doing. Tell God the truth about your anger and hurt—don’t hold back, not one, little bit. Your anger and hate belong before God. But then I’d ask you to pray for the one who has wounded you or for the faceless mass of strangers you’re so suspicious of. That’s what I think we should have done at the bedside of that dying Nazi soldier. That’s what I think we need to do this morning.